Weapons Still Don’t Make War

Colin S. Gray notably claimed that “weapons don’t make war.” Gray did not mean that no relationship existed between weapons, policy, and strategy, but that as instruments, weapons only have meaning in the context of policy and strategy. While this idea seems intuitive enough, it is easily muddled; particularly when weapons appear to provide technical solutions, policymakers and strategists may be tempted to abdicate their duties by substituting a weapon for a policy or strategy.

One significant part of the problem is that analysts and advocates alike can be tempted to impute weapons with certain political, strategic, and moral considerations that do not derive from some inherent aspect of the weapon itself. This problem is rampant in commentary on drones. Even in the most cogent critiques, analysts often imbue drones themselves, rather than they ways they are wielded, with a sinister quality that has little do with drones as drones, and more to do with drones as a stand-off strike platform being deployed in a targeted killing campaign.

Imbuing drones with strategic or political qualities they do not actually possess distorts discussion of the targeted killing campaign. Firstly, it feeds into a false narrative that targeted killing is easy and cheap, when in fact it involves massive amounts of hardware and personnel. Witness the casual calls by some commentators for the U.S. to simply put Assad on a drone “kill list,” as if Syria’s significant air defenses would not pose any problem for drones which have never had to brave the hostile firepower of a state-equipped military. Secondly, it needlessly injects irrational fears and erroneous thinking into all discussion of drones. Few Americans worry about the fact that military-grade assets such as helicopters and light aircraft have been frequent fixtures of American law enforcement, and even fewer think these would ever be deployed against Americans they way they are against enemies in a war zone. Yet such logical leaps pervade drone commentary, inserting a bizarre suspicion into the discussion of all unmanned systems, despite the fact that military operating concepts for unmanned systems treat them primarily as an additional, useful tool to fill already established operating parameters and military missions.

Murtaza Hussain’s recent article in Salon serves as a good example of this common sort of drone analysis. Hussain rightly recognizes that unmanned aerial systems (UAS) follow in the footsteps of millenia of human innovations in the quest to find a way to kill hostile humans more effectively with less harm to oneself, but still insists that drone warfare is “particularly insidious,” for three primary reasons.

First, Hussain argues, drones inherently undermine the Geneva Convention, specifically, Article 41 of Protocol I, which prohibits killing of those “hors de combat.” Since a potential drone target cannot surrender to an unmanned aerial system, there is no choice but to kill them.

Is this an inherent quality of a drone? There is no opportunity to surrender to a sniper whose location is unknown to his target, and who may not be in a position to take his target prisoner anyway. There is no opportunity to surrender to a mortar bombardment. There is certainly no opportunity to surrender to a Tomahawk Land Attack Missile, or the precision-guided bomb of a B-2 stealth bomber. The inability to surrender to a drone is not a problem unique to drones, or even particularly insidious, but a context, in some cases, of the way we may choose to employ a stand-off weapon, and not one that is all that morally or legally questionable. –

Rule 47. Attacking persons who are recognized as hors de combat is prohibited. A person hors de combat is:

(a) anyone who is in the power of an adverse party;

(b) anyone who is defenceless because of unconsciousness, shipwreck, wounds or sickness; or

(c) anyone who clearly expresses an intention to surrender;provided he or she abstains from any hostile act and does not attempt to escape.

‘Hors de combat’ status is determined not by the type of weapon, but by the military circumstances. For example, in the controversy over an American attack helicopter killing Iraqis who appeared to be surrendering, it may not have been possible to establish clearly that they were. Throwing up one’s hands but then getting back in a vehicle and traveling is not surrender, since retreating or fleeing is distinct from surrender under international law. Virtually no signatory of the Geneva Convention believes there is an unmitigated legal obligation to accept surrender in circumstances where receiving surrender is militarily impossible or would impose significant risks to personnel granting quarter.

The issue with drone strikes is not that unmanned systems carry them out (any stand-off weapon would face this problem), but that, outside the use of drones as close air-support in Afghanistan, drones are being deployed with only minimal special operations and covert personnel on the ground. That is, it is the nature of the conflict-a series of covert, clandestine, and stand-off strikes outside the context of a major conventional ground deployment-that causes these issues. And, indeed, looking in the larger context of the targeted killing program and the types of organizations they target, the much bigger - and more blatant - issue is the relentless violation of Article 41, which prohibits combatants to engage in perfidy, and which contributes to the next problem Hussain outlines.

As Hussain correctly notes, much reporting about the drone program indicates that their massively increased precision compared to other weapons systems is not particularly useful if the U.S. fails to discriminate between combatants and non-combatants for want of adequate intelligence. The problem of which Hussain speaks is one of any force confronting an enemy which flirts with violations of international humanitarian and customary prohibitions against perfidy. This Any veteran of Iraq or Afghanistan could explain that identifying legitimate combatants and targets is difficult even with troops on the ground. The moral issue at stake here - killing a potential noncombatant because their behavior may indicate hostile attempts at perfidy - has very little to do with the platform itself. If anything, drone operations, which occur in concert with manned Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft, prolonged surveillance, and ground-based covert or clandestine units, provide more opportunity for discrimination than simply lobbing TLAMs or JDAMs would (or conduct ascribed even to men with boots on the ground after curfew in purported “free fire zones” or “Indian Country” in Vietnam). It is not a problem with the so-called drone war, even less drones.

I say so-called drone war because that term fundamentally replaces context and analysis of the war with the weapon most publicly associated with it, significantly contributing to my issue with Hussain’s third point, which is that drones are insidious for enabling a “no cost” form of warfare. As one of this blog’s guest posters has pointed out for Foreign Policy, while drones may be cheaper than using other types of weapons for the same mission, that does not make the mission cheap. The argument that drones make war more likely, or let it persist for longer, does not hold up to any serious scrutiny.

The notion that somehow drones created low-risk, low-scrutiny warfare lacks historical or contemporary perspective. If there were no unmanned systems, casualties would still be low, and a massive targeted killing campaign could still be affordable, albeit with a slightly different execution. Open-ended authorizations of force for clandestine programs pre-date drones and do not require them. It’s not even as if drones allowed such secret wars to employ aircraft, either - the notion of a secret CIA air force precedes drones by decades.

That these campaigns are “low risk” has less to do with drones and more to do with the fact that the governments of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia are all basically acquiescent, tacitly or overtly, with Americans killing suspected terrorists or insurgents inside their borders, and that the targeted insurgents lack the military equipment or tactical acumen to inflict serious casualties on such a force. This targeted-killing program, employing a wide variety of air, land, and sea-based, manned and unmanned, overt and covert assets, is enabled by the unrelenting U.S. desire to kill terrorists and an open-ended legal authorization or acquiescence from Congress and the public. When Hussain argues:

Thus to a degree unprecedented in history the advent of drone warfare has given the government a free hand to wage wars without public constraint and with minimal oversight

he is doubly incorrect. The “nature” of the targeted killing program is inherent in the targeted killing, not drones or even “drone warfare,” since high-value targeted killing campaigns can take place with anything capable of lobbing a warhead to a forehead. And furthermore, the kind of conflicts we are seeing now are, by any empirical metric, not unprecedented in their lack of public oversight, their duration, or material constraints, regardless of platforms.

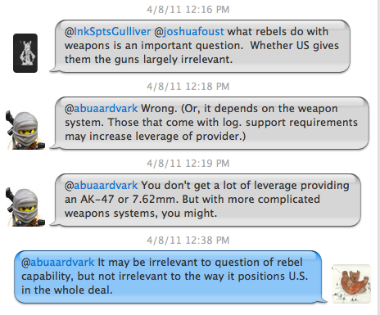

Another common fallacy of the sort of thinking that ascribes strategic or moral values to weapons or weapons systems is that of “lightly” or “defensively” arming foreign irregular groups, particularly in Syria. Critics who oppose arming Syria’s rebels rightly note that arms do not inherently constrain the purposes of human beings using them, and fear that adding more weapons to a major civil war could lead to post-conflict arms trafficking and their use in less-than-desirable activities, such as terrorist attacks, reprisal killings, continued internal violence, and attacks against the arming powers’ own interests.

The problem with linking arms provisions with defense of safe zones or protection of civilians is that there are no weapons systems that cannot be used to violate these intentions. Particularly with weapons that individuals or small groups can transport and operate on their own, speaking of an “offensive” or “defensive” weapon is foolish. A man-portable surface-to-air missile is defensive when it shoots down a helicopter strafing a rebel position, but it is offensive when its users encamp outside an airfield and use it to shoot down a landing transport or airliner.

The behavior of armed factions in Syria will be determined by their interests and the strategic context in which they seek to achieve them. Weapons are only part of that strategic context, and they are not a driving or controlling factor. For example, one justification analysts such as Anne-Marie Slaughter and others have long used for arming the Syrian rebels is that this would enable the creation of “safe zones,” but safe zones may not be the best military or political strategy for the rebels. If they believe taking those weapons and waging a continued guerrilla campaign that focuses on exhausting the regime as the goal, and considers the protection of civilians a secondary priority, then providing nominally “defensive” weaponry enables an offensive campaign.

When Slaughter and many others argue for providing “anti-tank, countersniper and portable antiaircraft weapons,” they are banking on several things. First, that whoever signs pledges to behave defensively actually means it and won’t manipulate foreign backers for their own interests. Second, that whoever signs the pledge has effective command and control down to the front lines where the weapons get used. Finally, that in the post-ceasefire or post-Assad stage, those weapons will not be used contrary to the desires of the rebels’ foreign patron. Characterizing the weapons as “defensive” or “light” does not eliminate any of these problems.

Consequently, arguments for arming the rebels often imbue the weapons with the intentions of the policy proponent. Take the following example. In this article, the author makes the case for providing RPG-7s and other light anti-armor weapons to the Syrian rebels, because they pose a low risk for post-conflict violence or a low degree of threat to the American counterpart to Syria’s tanks - the M1 Abrams. This is a perfect example of ascribing implicit political and strategic characteristics to a weapon rather than the context of its use: provide RPG-7s for destroying tanks, and dismiss it as a threat because post-conflict violence is less likely to involve tanks, and the weapon in question does not seem dangerous to American tanks.

It could not be more misleading. RPG-7s can do serious harm to virtually every other vehicle in the American land arsenal, and not only that, they have done serious harm to American aircraft, such as the Black Hawk helicopters in Mogadishu or, more recently, Extortion 17. RPG-7s have very short arming ranges, which make them particularly useful for urban combat, and they have more than enough firepower to destroy cars and armored personnel carriers, or to attack targets inside buildings. The number of terrorist attacks involving RPG-7s likely numbers in the tens of thousands. Simply because rebels received them to kill Syrian government tanks hardly means they cannot make use of them in a post-conflict environment. Nor, under the criteria of the safe zone advocates, would they necessarily make safe zones feasible. They hardly solve the issue of Syrian artillery, and anyone familiar with the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan can explain how RPGs, along with improvised explosive devices, mortars, snipers, and other weapons systems, can enable tactics to further a guerrilla movement or terrorism.

It is not only when discussing the arming of rebels that weapons are used as totems for broader discussions of policy. In Libya, Syria, and many other conflicts, the use of air power is often seen as a signal that a government’s suppression of a rebellion is reaching some sort of policy-relevant turning point. Aerial defections receive nearly as much attention as political defections. But why should that be? Air power may be used for indiscriminate bombings, but few regimes rely on their air power for conducting such operations. Nor is the air force the critical element of regime military strength. Indeed it is their artillery, as Brett Friedman explains, that provides the backbone of their killing power in operations for reducing cities. Pro-regime paramilitaries operate without much in the way of heavy weapons, let alone airpower, yet we frequently hear - from the highest levels of government - that it is helicopters that will “escalate the conflict quite dramatically.” What does this actually mean?

The primary effect of helicopters appears to be psychological. The greatest amount of violence will come from more mundane weapons, and the story of Syrian air power is hardly the bellwether of the Syrian civil war. Overly focusing on Syrian air power not only distracts from the more important drivers and dynamics of conflict, it also distorts discussion of potential policy solutions.

Calls for “no fly zones” over Syria play into a problem that is at least relatively easy for Western powers to solve - taking the Syrian air force out of operation - but will likely not produce meaningful strategic or political results. If the object of an intervention in Syria is to prevent the government’s reduction of urban centers or end the violence, merely targeting Syrian air power is not a particularly effective way of doing so, since such actions would not immediately or effectively impede the action of the more critical Syrian ground forces. If a certain type of intervention is unlikely to be efficacious in actually achieving our overall aims in a conflict, that is important to know. Focusing on a weapon system rather than the strategic context and outcomes impedes that process significantly.

Gray’s statement holds true. Weapons still do not make war. They are wielded and directed by humans against those of an opposing force or forces, in the midst of a host of mitigating factors, to achieve strategic aims. When Gray made his argument, he was challenging the notion of “strategic weapons” - weapons which have much more credible claims to transformative power or unique political or strategic quality than any of those discussed here - but even they are ultimately still devices whose meaning for politics, policy, and strategy derives from that broader ensemble of factors. Understanding what weapons systems are capable of is absolutely important for determining what kinds of strategies and policies are feasible, but they must be viewed as instruments subordinate to established ends. While weapons may appear easier to grasp than the complexities of warfare and the even more multifaceted issue of war, they should not take a lead role in coloring our analysis of policy.