Yesterday I wrote about a graphic posted to jihadi forums that garnered some media attention. In it, New York City’s famous skyline at sunset was overlaid with the text: “Al Qaeda: Coming Soon Again in New York.” The print media interpreted the graphic as a possible threat; on Fox News, Rep. Peter King was reportedly shown the image and asked if another attack was coming. I cautioned in my initial New York Daily News column and blog entry that the chance of this being the prelude to another large-scale attack was quite low. “With the recent disruption of large-scale plots, al Qaeda’s need for secrecy will only grow,” I wrote. “The chance of some low-level figure knowing enough about an upcoming plot connected to al Qaeda’s core to post a Photoshopped graphic boasting of it in advance is infinitesimally small.” It turned out, when more information came in, that the graphic wasn’t even a threat at all: if you read the Arabic-language introduction where this photo was posted on jihadi forums, it specifies that the graphic is actually a lesson in Photoshopping.

I got into an interesting discussion on Twitter thereafter about the effectiveness of terrorist threats (because they can garner media attention and either scare people or divert policing resources even when, as with the New York graphic, they are either phantom threats or not really threats at all). I think the conventional wisdom on this point is that jihadis have a relatively easy time getting the media to hype non-existent threats. As is so often the case, I took a position contrary to the conventional wisdom: I think the media’s hyping of questionable terrorist threats is in fact less common than is generally perceived.

To be sure, at one point amorphous threats received a disproportionate amount of national media coverage. But I think the general perception of how often this happens was set relatively early after the 9/11 attacks, when terror alerts were common and the media would devote a great deal of attention to each one. Since 2006, you would be hard pressed to name many examples of inordinate national media attention to threats that don’t exist. The New York City graphic is a recent example, but the kind of attention it garnered honestly isn’t all that impressive. Back in September, more attention than I would have liked was devoted to an alleged plot that would coincide with the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. A militant had fed the bogus story of a new plot to American officials, and it was widely reported. But before that? You would be hard pressed to name the last time, prior to September 2011, that a phantom threat truly received disproportionate national media attention.

In October 2010, a plot to carry out multiple Mumbai-style plots in Europe received a great deal of media coverage — but this represented a disrupted plot, and a large-scale one, rather than a hyped phantom threat. In the summer of 2010, I appeared on a rather remarkable Fox Business segment premised on the idea that “as many as hundreds of members” of Shabaab were slipping into the U.S. through its southern border (the other guest accused me of secretly aiding Shabaab when I cast doubt on that dubious assertion). But that segment can hardly be considered a major national media storm.

My point is not that phantom or amorphous threats do not get hyped — they do — but rather that this doesn’t happen as frequently as most people who follow terrorism closely perceive to be the case. Just as the point of not hyping amorphous threats is that we shouldn’t lose our sense of perspective, we also shouldn’t lose our sense of perspective about the media’s tendency to hype such incidents: it has happened far, far less frequently since the first five years of the “global war on terror.”

In fact, I think we can pinpoint the last great phantom threat with some precision. I believe it occurred in October 2006, when a warning was posted to the Internet message board 4chan that “America’s Hiroshima” was imminent. The message stated:

On Sunday, October 22nd, 2006, there will be seven “dirty” explosive devices detonated in seven different U.S. cities; Miami, New York City, Atlanta, Seattle, Houston, Oakland and Cleveland. The death toll will approach 100,000 from the initial blasts and countless other fatalities will later occur as a result from radioactive fallout.

These dirty bomb explosions would allegedly take place at NFL stadiums, during the games. The 2006 midterm elections were just around the corner, and Media Matters (an organization with which I have considerable political disagreement) has a decent rundown of the kind of media attention this threat received. “CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC dedicated a considerable amount of airtime to a purported threat to NFL stadiums in seven cities,” Media Matters stated. The Media Matters writeup notes that I was interviewed about this threat — appearing on Fox News’s The Big Story — but I wish it had also reported on the content of my appearance, if only because it departed significantly from the cautious way that other commentators treated this “news” item. I said on air that we could be absolutely certain that this threat was bogus — for the same reasons that we could be certain the “Coming Soon Again in New York” graphic wasn’t our first warning of another 9/11. Leave aside the ridiculous claim that the initial death toll from seven dirty bomb blasts would be 100,000 — it most definitely would not — and it is still obvious that this threat was a hoax. Quite simply, if al Qaeda was really prepared to set off dirty bombs simultaneously in seven different cities, would some chump who’d go bragging about the operation on 4chan really be given advance notice? I guess there’s the possibility that this could have been an official al Qaeda announcement — but given the fact that the jihadi group had just seen a large-scale plot disrupted (the August 2006 transatlantic air plot), would it really provide such specific information about where it would strike, such that authorities’ chance of disrupting the plot would be maximized? And if we want to assume that this might have been an official al Qaeda announcement, since when had 4chan, of all places, become al Qaeda’s go-to channel for communication?

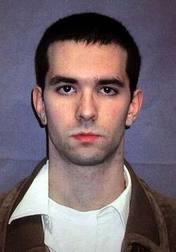

A few seconds of thought could thus easily reveal that there was no meat to this story, and I said as much on the air. But the NFL “plot” is so much more hilarious when you know the actual back story. This wasn’t the phantom threat of committed jihadis or their supporters. Rather, the 4chan message was the work of Wisconsin resident Jake Brahm, who was at the time living with his parents and working part-time at a grocery store. Essentially, he was bored and wanted to see if he could cause a bit of a stir by making some juvenile online threats. Before that, Brahm was best known for keeping a personal blog of his masturbatory habits entitled “Jake Brahm Wangs Da Poo.” Sadly, it’s no longer available online — but really, you probably didn’t want to read it in the first place. Brahm ultimately plead guilty to willfully conveying false information, and was sentenced to six months in federal prison. This is the man who briefly scared the whole country:

I think Media Matters was right to link the excessive coverage of Brahm’s self-evidently bogus threat to the 2006 midterm elections. But the bottom line is that this media attention didn’t swing the election, at all. The Republicans, at the time generally considered the tougher of the two parties on terrorism, were trounced at the ballot box; and the media looked awfully silly for how much time it devoted to Brahm’s little cry for attention.

I think Media Matters was right to link the excessive coverage of Brahm’s self-evidently bogus threat to the 2006 midterm elections. But the bottom line is that this media attention didn’t swing the election, at all. The Republicans, at the time generally considered the tougher of the two parties on terrorism, were trounced at the ballot box; and the media looked awfully silly for how much time it devoted to Brahm’s little cry for attention.

This is a decidedly non-scientific judgment, but I think an analysis of the media’s coverage of vague, amorphous terrorist threats would reveal Brahm’s NFL warning to be the last great phantom threat. I’m not saying that threats have never been hyped since, but rather that to me October 2006 seems to represent the apex of the practice, with terror alerts and random but suggestive data points garnering declining attention thereafter.